“The mother of W. Steele, [Susan] Lowdermilk, was a daughter of the late Robert J. Steele, a member of the old and well-known Steele family of Richmond County, and whose name appears prominently on the pages of North Carolina’s history. Robert J. Steele was a grandson of Robert Johnson Steele, who was born at Carlisle, Cumberland County, England, and who, as a very young man, came to America as a soldier of the English army of Lord Cornwallis. He was badly wounded and left for dead on the field of the battle of the Brandywine, and there was picked up by a daughter of Dr. Richard Grubbs, who noticed him as she was passing by in a carriage. She carried him to her home, where he was attended by Doctor Grubbs, who was a surgeon in the Continental army. After the war, he came to North Carolina, first locating in Granville County and afterward removing to Montgomery County…”

War and its aftermath have a way of changing the fighting man, and in such times of transition, many British Loyalists turned, for reasons like those this soldier encountered. Having no knowledge of his wounds or of his path to healing, I can imagine Robert J. Steele’s suffering and how it followed him going forward.

Robert Steele was indeed a wealthy man; excluding acquisitions in Anson and Richmond Counties, he received 27 land patents in Montgomery County, almost all of which were located on the east side of the Yadkin River. Speculating broadly on land for resale value, only one tract he patented was located west of the Yadkin, in what is now Stanly County.

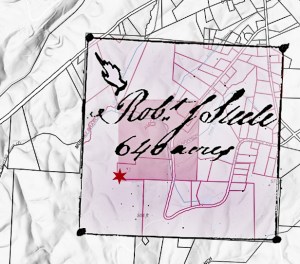

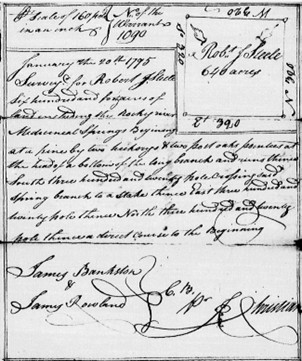

In 1794, Robert J Steele warranted a survey for “640 acres on the So. Side of the Pee Dee River on the waters of the Rocky River, including the Medicinal Rocky River Springs.” The land was surveyed the following year, with the patent being formally issued in 1798. Serving as chain bearers in support of the survey were James Bankston and James Rowland, who were early figures significant to the development of the Long Creek Watershed.

In 1794, Robert J Steele warranted a survey for “640 acres on the So. Side of the Pee Dee River on the waters of the Rocky River, including the Medicinal Rocky River Springs.” The land was surveyed the following year, with the patent being formally issued in 1798. Serving as chain bearers in support of the survey were James Bankston and James Rowland, who were early figures significant to the development of the Long Creek Watershed.

Some people mistakenly believe that land grants across North Carolina were freely given …or were awarded for bravery and service during the American Revolution. Our state’s records do not support that claim. Apart from land grants issued beyond the mountains, which were awarded to soldiers who met the basic requirements, no land within the boundaries of today’s North Carolina was granted as payment for military service. The rationale for early land grants across today’s North Carolina lies instead in related fees, population growth and movement, and projected revenue from ownership and the accrual of property taxes.

Clear in law and intention, I’d like to return to the story of Robert J. Steele, a proper British fellow who served under General Cornwallis, the feared leader portrayed by actor Tom Wilkinson in The Patriot. Our state is built on blood and separation from our beginnings. We owe much to loyalists such as Steele, who, at their own discretion, chose to sever their earlier ties to England. So, here I imagine a powerful man, gutted and clearly dogged by injury. Kindness and a young woman’s chance encounter may have led to his rebirth of sorts. I can also imagine the role of naturally flowing medicinal waters during his time of healing. Robert J. Steele likely exploited mineral-rich medicinal springs, and he may have been the first to develop them into what they are remembered today in Stanly County. Robert Johnson Steele undoubtedly benefited from the waters, and I can imagine a man of his stature building a house or retreat there to enjoy and share what may have been a very different sort of business venture. However, in the end, he and his family lie at rest in the Ledbetter-Steele Cemetery, north of the confluence of the Little River and the Great Pee Dee River.

Word of Robert J. Steele’s investment spread instantaneously as the water was called out pictorially in a survey for an extensive patent of land occurring at the same time. Drawn in 1795 on the survey for 17,920 acres to be issued to speculator Thomas Carson and William Moore, the “medicinal springs” appear in the vicinity known today as “Rocky River Springs.”

Word of Robert J. Steele’s investment spread instantaneously as the water was called out pictorially in a survey for an extensive patent of land occurring at the same time. Drawn in 1795 on the survey for 17,920 acres to be issued to speculator Thomas Carson and William Moore, the “medicinal springs” appear in the vicinity known today as “Rocky River Springs.”

Many articles have been written about Rocky River Springs, and much has been gleaned from the writing. The most telling of which might be found within an article published in the June 11, 1884, issue of the Baptist newspaper called the Biblical Recorder:

-ROCKY RIVER SPRINGS-

A few weeks ago, we went by invitation from the proprietor, Rev. C. C. Foreman (himself a Baptist minister), to this favorably known Stanly County watering place, to preach on Sunday morning. We were wonderfully “taken” with the loveliness of this favorite summer resort, the medicinal virtues of whose health-giving springs have been tested and proved beyond all doubt to be exceedingly beneficial in their curative power over all scrofulous and kidney affections.

We preached in the Academy of bro. Bigger, who, besides being a successful teacher and Principal of a flourishing day school, is also a most useful and zealous worker in Rocky River Spring Sunday school, over which he presided as an efficient Superintendent.

A large and ably hotel with a bountiful table supplied with the choicest viands to tempt the sluggish appetite; and scenery diversified with hill and dell; and rocks and flowing streams with magnificent shade trees for outdoor retreat of the invalid, are a few of the attractions of “Rocky River Springs.”

As part of my county-wide mapping project, I wanted to learn more about this place, particularly during the period 1794-1841, before the formation of Stanly County and its transition from Montgomery County, whose records were destroyed by arsonist Elijah Spencer. Deed books and records in Stanly County indicate that understanding Jones Green’s life may be the best starting point for this chapter of the story.

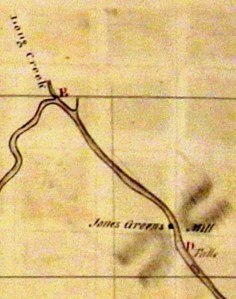

Before digging deep into Stanly County land records, Jones Green is spotted in location on another period survey map completed in 1820 by order of the General Assembly. At that time, the state considered making the Rocky River navigable to recoup revenue from goods shipped down the Pee Dee River to South Carolina. A detailed look at this valuable map illustrates the area downstream of Long Creek, including “falls” and a mill operated by Jones Green. According to a last will dated 1842, Jones is the son of David Green, whose ancestry is not fully understood.

Before digging deep into Stanly County land records, Jones Green is spotted in location on another period survey map completed in 1820 by order of the General Assembly. At that time, the state considered making the Rocky River navigable to recoup revenue from goods shipped down the Pee Dee River to South Carolina. A detailed look at this valuable map illustrates the area downstream of Long Creek, including “falls” and a mill operated by Jones Green. According to a last will dated 1842, Jones is the son of David Green, whose ancestry is not fully understood.

And now to land records, in 1840 a person called John D. Witherspoon is identified in the tax list as owning 99 acres described only as “R. R. Springs.” And then, in 1853, John D. Witherspoon of Darlington County, South Carolina, apparently gifted the same land “in which the medicinal springs known as Rocky River Springs is situated.” The land was given “in consideration of the goodwill which I have for Jones Green and his wife.” What should have been a gift conveyance of 100 acres was for only 99 acres because John D. Witherspoon apparently cut off one acre from the extreme southwest corner to “secure to them a home during their lives.” Following the eventual deaths of Jones and his wife, the land, with the 99 acres included, passed to their sons W. H. D. (Henry Deberry) Green and A. J. “Andrew Jackson Green.

John D. Witherspoon held Jones Green in high regard, and just as with Robert Johnson Steele, John D. Witherspoon was an important person. For reasons similar to Steele’s, Witherspoon undoubtedly benefited from the healing waters in Stanly County, but there is more to his story. That’s because, in addition to being recorded as deeding land for the historic library and as a founder of Society Hill in Darlington County, South Carolina, today the Witherspoon Island Conservation Easement protects over 3,000 acres along the western shore of the Great Pee Dee River. This effort aims to protect an Oxbow Lake and over 20 miles of earthen dikes built by J. D. Witherspoon in the mid-1800s. Digging deeper into the family’s history, an online report revealed the following about John D. Witherspoon’s paternal grandfather. Using artificial intelligence:

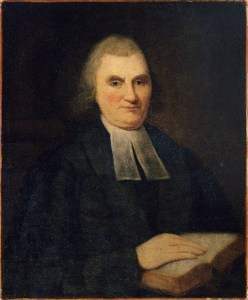

John Witherspoon (1723-1794) was a preeminent Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, educator, and Founding Father who served as the president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) from 1768 until his death in 1794. He merged Presbyterian evangelism with Scottish Enlightenment thought, arguing that personal religious awakening was crucial to civic virtue. He was the only clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence and a key figure in organizing the Presbyterian Church in the United States, moderating its first General Assembly in 1789.”

John Witherspoon (1723-1794) was a preeminent Scottish-American Presbyterian minister, educator, and Founding Father who served as the president of the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) from 1768 until his death in 1794. He merged Presbyterian evangelism with Scottish Enlightenment thought, arguing that personal religious awakening was crucial to civic virtue. He was the only clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence and a key figure in organizing the Presbyterian Church in the United States, moderating its first General Assembly in 1789.”

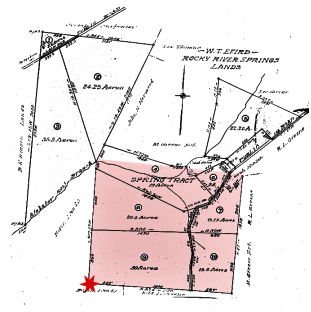

In addition to all of this about the neighborhood of Rocky River Springs, I’ve begun mapping the surrounding land, where a 1935 property plat for W. T. Efird provides the best starting point.

Called out as “W. T. Efird, Rocky River Springs Lands,” the red-shaded area encompasses the 99-acre tract deeded back to the Jones Green family by J. D. Witherspoon. Note that the aging Jones Green and his wife should have lived out their lives on an acre set aside for the purpose if the intent of John D. Witherspoon’s gift was properly honored (see red star). And, in the 1790s, the medicinal springs would have been buried within the larger 640-acre tract issued to Robert Johnson Steele, as shown on today’s Stanly County GIS map.

Much more can be said, but for now, the next time you find yourself at the Rocky River Springs Fish House, seated and waiting for your plate of flounder and slaw to be served, think of Robert J. Steele, John D. Witherspoon, and of Jones Green. At some point in time, these men likely sat nearby, and their journeys in life may genuinely be part of yours.

Much more can be said, but for now, the next time you find yourself at the Rocky River Springs Fish House, seated and waiting for your plate of flounder and slaw to be served, think of Robert J. Steele, John D. Witherspoon, and of Jones Green. At some point in time, these men likely sat nearby, and their journeys in life may genuinely be part of yours.